One of the attributes to a famous artist most overlook is their humanness, the attributes that make us a human being. Did Shakespeare have a best friend? Did Chaucer enjoy drinking tea? Did Homer ever have a lover? Artists become a figure of greatness to most, a position which tends to dehumanize them.

Peter Doyle and Whitman were intimate friends, so intimate, some believe the two may have been lovers. After reading about Doyle's life, it becomes apparent why a writer would have cherished him, not only as an individual, but also as a type of muse. Doyle, a commonly educated man, was a soldier, prisoner of war (which he escaped from), an attendee of the play where Abraham Lincoln was shot, a street car worker, a railroad worker... Basically, Doyle was a figure Whitman could view as a flawless American, one who experienced nearly every huge historical feat of the century.

The two sent a group of letters back and forth, which were stored and later published. One interesting aspect to this publication is the type of fame Doyle was able to recieve merely by being a friend of Whitman. Reviewers of the letters initially wished there were more written by Doyle! It's fairly interesting to think a relatively unliterate man draws forth more reader interest than one of the most famous poets history has to offer.

Regardless of fame and historical acclaim, the two had one of the best relationships in literary history. Doyle's emotional attachment to Whitman is, to say the least, touching. Doyle recounts his attempts to keep Whitman alive even after death, merely to be close to the man.

"I have Walt's raglan here [goes to closet—puts it on]. I now and then put it on, lay down, think I am in the old times. Then he is with me again. It's the only thing I kept amongst many old things. When I get it on and stretch out on the old sofa I am very well contented. It is like Aladdin's lamp. I do not ever for a minute lose the old man. He is always near by. When I am in trouble—in a crisis—I ask myself, 'What would Walt have done under these circumstances?' and whatever I decide Walt would have done that I do."

Upon his passing, Whitman gave Doyle a silver watch. This silver watch signifies not only the lasting friendship of the two, but also stands as a symbol for the duration of time Whitman and Doyle had been friends. A fairly beautiful friendship, one which shines brighter than silver and is worth more than gold.

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

Rereviewing Reviews and Reviewers

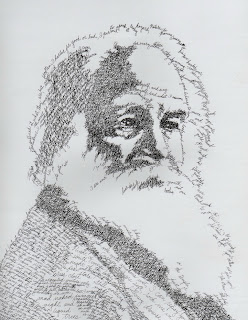

For my next major project, I shall either approach the reviewers reviews of Whitman's Leaves of Grass from a few specific schools of criticism, or I will paint a type of word portrait of Whitman utilizing text from his Leaves of Grass. While the first will expand my knowledge of modern day techniques of criticism, the second will increase my knowledge of Leaves of Grass through a careful selection of thematic phrases, while also developing my artistic abilities. To expand on both ideas, I wish to approach reviews of Whitman's text because it becomes a type of exponential learning, reflecting on anothers reflections. Also, varying forms of criticism are fairly central to the modern day literary scene, such as deconstructionism, new historicism, formalism, and even types of psycho-semantics. This would prove helpful because I would become more familiarized with directions literary critics take while sorting through literary works. A painting, however, could prove extremely aesthetically pleasing, while also promoting this type of hybridity which overwhelms todays artistic front. Combining various artforms, here poetry and painting, would expand both markets, as well as allowing me to freely delve between fairly rich artistic material. Artistically speaking, there are a series of techniques which would be integrated to derive a completely unique creation. My only limitations are my current lack of photoshop, which would open doors to craft a type of 3D image (possible utilizing calculus, too, just less precise).

Would require further research of outside critical techniques, or a focus primarily on Whitman's text. Essentially, each would prove to be a powerful learning process, they simply focus on two different types of art- one visual, and one textual.

Would require further research of outside critical techniques, or a focus primarily on Whitman's text. Essentially, each would prove to be a powerful learning process, they simply focus on two different types of art- one visual, and one textual.

Monday, March 12, 2012

Whitman's Popularity

Word portraits are the classiest, let's be real. Whitman's face created from the face of words thrown across a page- what could be more hip? The portrait, aside from being unparalleled in its level of coolness, reinterprets poeticism in an extremely unique way... Here, a poet is viewed as a composition of his words, a carefully shaped and precise selection composing a snapshot image of themes and poeticism. Most view poems as extensions, here, the artist reinterprets poems as a composition of a poet.

Artist of Word Portraits- John Sokol, Alyssa Pelletier

http://www.johnsokol-artist-author.com/index.html

http://alyssapelletier.com/

Martin Tupper: Didacticism

Martin Tupper, a poet from Whitman's time era, represents a genre paralellism- IE a style of writing growing onto another branch of poetries trunk. Martin Tupper focused on morality, a didactic approach toward teaching masses stronger moral values than was prevalent- a difficult yet noble cause. Whitman's own genre, mostly free-verse celebratory poetry, tends to stray away from overt didacticism, focusing on celebrating the positive aspects of life rather than critiquing moral mistakes of the past. These two writers provide valuable insight toward what made Whitman popular, canonized, and remembered, whereas Tupper remains relatively in the wake of Whitman's allegorical power-boat. I would argue this happened from something fairly and simply- genre. Whitman strayed away from teaching entire groups morality, something most believe to be intrinsic, innate, and extremely relative. People, generally, dislike being told how to behave, what actions are socially "correct" and "incorrect," or to have another bash each decision that they make with an air of sophisticated morality. Whitman's morals are weaved into the threads of his texts, being exposed through character actions, narrative restraint, dictorial selection; whereas Tupper provides clear religious and moral instructions,

"Despise not, shrewd reckoner, the God of a good man’s worship,

Neither let thy calculating folly gainsay the unity of three:

Nor scorn another’s creed, although he cannot solve thy doubts;" (Of a Trinity).

His work tells how, it does not recount how. Whitman's tales, on the other hand, recount a narrative structure, a way of life, an individual experience- He does not appear to wish for his readers to behave in the same manner, no, he celebrates their differences. Whereas Martin Tupper seems to wish for each reader to follow the same moralistic and religious guidelines as his narrator. These two differences explain not only what gained Whitman more support in his generation, as well as those which followed, but also divulged important information as to persuasive and rhetorical techniques utilized by institutionalized churches (represented through Tupper). Rather than celebrating differences and recounting favorite personality and charactorial types, it provides a routine, a copy-pasted structure of similarness, it strives to craft identities to not necessarily become identical, no, for this would be too obvious and perfect to them, but instead to formfit each individual to follow structural and overarching guidelines. Whitman gained support because he restrained from telling people how to behave, whereas Tupper gained some sort of inner-satisfaction supporting an institutionalized life path. Each benefits in their own respect, however, Whitman seems to have attained the popular vote, so to speak.

"Despise not, shrewd reckoner, the God of a good man’s worship,

Neither let thy calculating folly gainsay the unity of three:

Nor scorn another’s creed, although he cannot solve thy doubts;" (Of a Trinity).

His work tells how, it does not recount how. Whitman's tales, on the other hand, recount a narrative structure, a way of life, an individual experience- He does not appear to wish for his readers to behave in the same manner, no, he celebrates their differences. Whereas Martin Tupper seems to wish for each reader to follow the same moralistic and religious guidelines as his narrator. These two differences explain not only what gained Whitman more support in his generation, as well as those which followed, but also divulged important information as to persuasive and rhetorical techniques utilized by institutionalized churches (represented through Tupper). Rather than celebrating differences and recounting favorite personality and charactorial types, it provides a routine, a copy-pasted structure of similarness, it strives to craft identities to not necessarily become identical, no, for this would be too obvious and perfect to them, but instead to formfit each individual to follow structural and overarching guidelines. Whitman gained support because he restrained from telling people how to behave, whereas Tupper gained some sort of inner-satisfaction supporting an institutionalized life path. Each benefits in their own respect, however, Whitman seems to have attained the popular vote, so to speak.

Plays and Operas, Too!

Whitman begins to provide insight as to which performances, writers, and composers crafted his artistic vision from an early age. Whitman posts names and artists almost like an advertisement, showing off his own musical and theatrical taste, becoming his own type of institutionalized advertisement. Furthermore, it begins to show the reader varying insights which have come together to form Whitman's poetic outreaching, an artistic style which stretches vastly through all fields of American life.

"And certain actors and singers, had a good deal to do with the business. All through these years, off and on, I frequented the old Park, the Bowery, Broadway and Chatham-square theatres, and the Italian operas at Chambers-street, Astor-place or the Battery -- many seasons was on the free list, writing for papers even as quite a youth. The old Park theatre -- what names, reminiscences, the words bring back!" (Plays and Operas, Too).

This business, if one were to put forth an educated guess, would seemingly be the business of developing as an artist. Here, we begin to see the influences and significance Whitman placed on other artists, instantaneously putting forth ads about them, as well as promoting them by presence. Whitman divulges a list, and, as one might expect, returns to his classical position promoting Shakespearian plays, which apparently have overarching influence on Whitman's work and enjoyment from an early age forth, "As boy or young man I had seen, (reading them carefully the day beforehand,) quite all Shakspere's acting dramas, play'd wonderfully well. Even yet I cannot conceive anything finer than old Booth in "Richard Third," or "Lear," (I don't know which was best,) [...]." Whitman blends a wide variety of artists, some from his time period, and some straying away from his own. This replicates Whitman's own diversity, plus, provides other artists with a tactful way of presenting artists, both ancient and new.

http://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=WhiPro1.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=14&division=div2

"And certain actors and singers, had a good deal to do with the business. All through these years, off and on, I frequented the old Park, the Bowery, Broadway and Chatham-square theatres, and the Italian operas at Chambers-street, Astor-place or the Battery -- many seasons was on the free list, writing for papers even as quite a youth. The old Park theatre -- what names, reminiscences, the words bring back!" (Plays and Operas, Too).

This business, if one were to put forth an educated guess, would seemingly be the business of developing as an artist. Here, we begin to see the influences and significance Whitman placed on other artists, instantaneously putting forth ads about them, as well as promoting them by presence. Whitman divulges a list, and, as one might expect, returns to his classical position promoting Shakespearian plays, which apparently have overarching influence on Whitman's work and enjoyment from an early age forth, "As boy or young man I had seen, (reading them carefully the day beforehand,) quite all Shakspere's acting dramas, play'd wonderfully well. Even yet I cannot conceive anything finer than old Booth in "Richard Third," or "Lear," (I don't know which was best,) [...]." Whitman blends a wide variety of artists, some from his time period, and some straying away from his own. This replicates Whitman's own diversity, plus, provides other artists with a tactful way of presenting artists, both ancient and new.

http://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=WhiPro1.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=14&division=div2

Rhetorical Omnipresence

Fifty Hours Left Wounded on a Field narrates Whitman's experiences speaking with a wounded soldier during the civil war. Similar to the section from Leaves of Grass where Whitman cares for a runaway slave, the entry balances between empathetic concern and unbiased tale renunciation. One of the most impressive aspects to Whitman's narrative technique is his ability to unfold a series of events without offering too explicit political stances- while the details may be skewed to support one side or the other, he rarely makes his own stance explicitly obvious. For example, he never says "I stand for the slaves stretching forth to receive freeness and liberty," he instead recounts his narratives utilizing specific details from his experiences to skew his story in a general direction, implicit and underlying,

"The runaway slave came to my house and stopt outside;

I heard his motions crackling the twigs of the woodpile;

Through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him limpsy and weak,

And went where he sat on a log, and led him in and assured him,

And brought water, and fill’d a tub for his sweated body and bruis’d feet,

And gave him a room that enter’d from my own, and gave him some coarse clean clothes,

And remember perfectly well his revolving eyes and his awkwardness,

And remember putting plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles;

He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and pass’d north;" (Leaves of Grass)

"Here is a case of a soldier I found among the crowded cots in the Patent-office. He likes to have some one to talk to, and we will listen to him. [...] He answers that several of the rebels, soldiers and others, came to him at one time and another. A couple of them, who were together, spoke roughly and sarcastically, but nothing worse. [...] But he retains a good heart, and is at present on the gain. (It is not uncommon for the men to remain on the field this way, one, two, or even four or five days.)" (Specimen Day Fifty Hours Left Wounded on a Field).

Each of these two tales, while different, retain an attempt at unbiasness- however, instantaneously expose the truth that no story could ever be unbiased, regardless of authorial talent. Each example of the story does not explicate too obvious of a position- he takes care of the slave, yet doesn't quite celebrate him. He feels empathy toward the soldier fighting in the war, but is tentative to admit which side he wishes to support. His stance remains ambiguous. However, even through this tale recount, one recognizes specific details and dictorial decisions which, ultimately, skew the story one way or another. For example, one might realize Whitman's talk(s) with a soldier extended into much more detail and subjects, techniques, political standpoints, post-war soldier insurance, importance of slavery, yet he consciously decided to narrate the soldier was left alone for days, met with soldiers who bad mouthed him (yet withheld from inacting violence), and that this occurance was normal. Just the same as Leaves of Grass includes several specific and chosen details- twigs breaking on a woodpile, the weak and sickly disposition of the slave, the duration of his visit, so on and so forth. Each of the two, while not explicitly taking political stances, evoke emotions such as empathy from the reader- empathy being a fairly persuasive technique, Whitman is able to alter the positions of his readers even without taking an overt position. These two entries highlight the idea that stories, regardless of a writers talent, always have some sort of rhetorical bias.

http://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=WhiPro1.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=25&division=div2

"The runaway slave came to my house and stopt outside;

I heard his motions crackling the twigs of the woodpile;

Through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him limpsy and weak,

And went where he sat on a log, and led him in and assured him,

And brought water, and fill’d a tub for his sweated body and bruis’d feet,

And gave him a room that enter’d from my own, and gave him some coarse clean clothes,

And remember perfectly well his revolving eyes and his awkwardness,

And remember putting plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles;

He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and pass’d north;" (Leaves of Grass)

"Here is a case of a soldier I found among the crowded cots in the Patent-office. He likes to have some one to talk to, and we will listen to him. [...] He answers that several of the rebels, soldiers and others, came to him at one time and another. A couple of them, who were together, spoke roughly and sarcastically, but nothing worse. [...] But he retains a good heart, and is at present on the gain. (It is not uncommon for the men to remain on the field this way, one, two, or even four or five days.)" (Specimen Day Fifty Hours Left Wounded on a Field).

Each of these two tales, while different, retain an attempt at unbiasness- however, instantaneously expose the truth that no story could ever be unbiased, regardless of authorial talent. Each example of the story does not explicate too obvious of a position- he takes care of the slave, yet doesn't quite celebrate him. He feels empathy toward the soldier fighting in the war, but is tentative to admit which side he wishes to support. His stance remains ambiguous. However, even through this tale recount, one recognizes specific details and dictorial decisions which, ultimately, skew the story one way or another. For example, one might realize Whitman's talk(s) with a soldier extended into much more detail and subjects, techniques, political standpoints, post-war soldier insurance, importance of slavery, yet he consciously decided to narrate the soldier was left alone for days, met with soldiers who bad mouthed him (yet withheld from inacting violence), and that this occurance was normal. Just the same as Leaves of Grass includes several specific and chosen details- twigs breaking on a woodpile, the weak and sickly disposition of the slave, the duration of his visit, so on and so forth. Each of the two, while not explicitly taking political stances, evoke emotions such as empathy from the reader- empathy being a fairly persuasive technique, Whitman is able to alter the positions of his readers even without taking an overt position. These two entries highlight the idea that stories, regardless of a writers talent, always have some sort of rhetorical bias.

http://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=WhiPro1.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=25&division=div2

Tuesday, March 6, 2012

Reviewing Reviews

"Here we have a book which fairly staggers us. It sets all the ordinary rules of criticism at defiance."

The foundation of the beginning review, entitled "Leaves of Grass- An Extraordinary Book," claims Whitman's text avoids all types of criticism, or to put it differently, by brinking the gap between classical formalaic poetry and his version of modernity, he was able to create something so staggeringly new that even to this day we struggle finding the tools to analyze and criticize it completely. Historically, Whitman's text gains much of its power from the fact that it avoids rhyme schemes, metricality, ordinary juxtaposition, poetic structure- it was the creation of free verse poetry. This free verse, one of the first true steps away from classicality, avoids ordinary rules and limitations for the very purpose of avoiding classical criticism. What this shift away from classical and formal poetry implies, being more a suggestion of Whitman's own individuality, is a general transformation of America's belief structure, a nation striving to find their own voice while resting on relatively new feet. America had no single poetic structure, no concrete form, every poem being a mere reflection on their pre-colonialized roots- Whitman provided an alternative mode to craft poetry while instantaneously promoting the core values of American ideals- a freeness unbound.

"It is a poem; but it conforms to none of the rules by which poetry has ever been judged. It is not an epic nor an ode, nor a lyric; nor does its verses move with the measured pace of poetical feet—of Iambic, Trochaic or Anapaestic, nor seek the aid of Amphibrach, of dactyl or Spondee, nor of final or cesural pause, except by accident."

The review transforms into a microscopic analyzation of minor poetic detail, however, the reviewer finds himelf without the capabilities to explain without utilizing a dialectic argumentative structure. Because Whitman's text is a paragon of newness, there are, for the most part, only new poetic devices; techniques one observes yet is incapable of describing. The reviewer begins to explain how the poem is devised by saying it merely does not make use of this, nor this, nor this. Such a reviewing technique explicates Whitman's enterance into poetic creation which is limitless and infinite.

"He does not pick and choose sentiments and expressions fit for general circulation—he gives a voice to whatever is, whatever we see, and hear, and think, and feel. He descends to grossness, which debars the poem from being read aloud in any mixed circle. We have said that the work defies criticism; we pronounce no judgment upon it..."

The finality of the essays core returns to the original claim- we pronounce no judgement on Whitman, we merely stand in awe at a poem which avoids classical criticism. Rather than focusing on lofty poetic classicalism, he focuses on thematically connecting with his American audience- intertwining themes touching on America's support of the "everyman," his providing a voice to every majority and minority, his celebration of freedom, and his attempts to stretch away from classical and outlandish thought.

________________________________________________________________________________

The second review, titled merely "Leaves of Grass," descends into a new realm of analysis, one which focuses not on poetic technique, but thematic power. The reviews have entirely divergent writing styles, the first a more traditional approach, the second a more Whitmanesque reflection. He begins by stating Whitman's world needed this- to paraphrase, a speaker who avoids genres, nomenclatures, institutionalized colonial remnants, a poet who stands away from socio-economic positions, a world which

"[...]needed a "Native American" of thorough, out and out breed—enamored of women not ladies, men not gentlemen; something beside a mere Catholic-hating Know-Nothing; it needed a man who dared speak out his strong, honest thoughts, in the face of pusillanimous, toadeying, republican aristocracy; dictionary-men, hypocrites, cliques and creeds; it needed a large-hearted, untainted,self-reliant, fearless son of the Stars and Stripes, who disdains to sell his birthright for a mess of pottage; who does

"Not call one greater or one smaller,

That which fills its period and place being equal to

any;"

who will

"Accept nothing which all cannot have their coun-

terpart of on the same terms."

The reviewers language is languid, rich, smooth and flowing like Whitman's own writing. This review also explains and reflects on Whitman's time period, explaining historically what they need. Here, the review takes an almost new historicism approach. Next, the reviewer begins utilizing poetic technique, a point of the review where structural criticism clashes with poetic alignment

.

"Sensual!—No—the moral assassin looks you not boldly in the eye by broad daylight; but Borgia-like2 takes you treacherously by the hand, while from the glittering ring on his finger he distils through your veins the subtle and deadly poison..

Sensual? The artist who would inflame, paints you not nude Nature, but stealing Virtue's veil, with artful artlessness now conceals, now exposes, the ripe and swelling proportions.

Sensual? Let him who would affix this stigma upon Leaves of Grass, write upon his heart, in letters of fire, these noble words of its author..."

This second review is powerful due to its poeticness rather than its criticism. An impressive review, to say the least.

________________________________________________________________________________

The third review criticizes (definitively speaks against) Leaves of Grass. This review, entitled [Review of Leaves of Grass (1855)], states that his work isn't even worth purchasing, much less, if we have it, we have some sort of a moral obligation to rid ourselves of it, descending the review, at least stylistically, into satire. As an audience, "We shall not aid in extending the sale of this intensely vulgar, nay, absolutely beastly book, by telling our readers where it may be purchased."

The reviewer then (humorously?) states the author ought to be "sent to a lunatic asylum" for "pandering to the prurient tastes of morbid sensualists." The reviewer seems to be claiming Whitman's poem descends into the sexual morbid, such as a lover entering into the chest of a lover, the famous lines where the author begs for his reader to pull on his beard and insert their tongue into his chest, and this bluntness allegedly qualifies a poet to descend across this fine line of genius and sanity, a position which is more frustrating than one may realize; it is, after-all, impossible to prove sanity one way or another for anyone. When put into this frame, one may begin to understand the fundamental critique satirically, at least so far as it is slightly morbid, even vulgar, but to send the author to a "lunatic asylum," is, while almost humorous, a pretty low blow and terrible critique.

The review then criticises Emerson, this time period's acclaimed didactic writer, for supporting Whitman.

"...indorsed by the said Emerson, who swallows down Whitman's vulgarity and beastliness as if they were curds and whey. No wonder the Boston female schools are demoralized when Emerson, the head of the moral and solid people of Boston, indorses Whitman, and thus drags his slimy work into the sanctum of New England firesides."

Instead of a celebration, this is more of an attack: stating a poet should be sent to an insane asylum, referring to his work as "slimy," even reaching to blame the demoralization of Boston's female schools on both Emerson (for supporting Whitman), as well as Whitman himself; it's a "view the cup as always half empty and poisoness" type of perspective.

In my humble opinion, an unhealthy review, although even us optimistic ones must sometimes hear opinions of negative ones to gain perspective.

Links to Reviews:

http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/reviews/leaves1855/anc.00012.html

http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/reviews/leaves1855/anc.00026.html

http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/reviews/leaves1855/anc.00030.html

Thursday, March 1, 2012

iam

(Relatively)Sept. 3. -- Cloudy and wet, and wind due east; air without palpable

fog, but very heavy with moisture -- welcome for a change. Forenoon, crossing

the Delaware, I noticed unusual numbers of swallows in flight, circling,

darting, graceful beyond description, close to the water. Thick, around the bows

of the ferry-boat as she lay tied in her slip, they flew; and as we went out I

watch'd beyond the pier-heads, and across the broad stream, their swift-winding

loop-ribands of motion, down close to it, cutting and intersecting. Though I had

seen swallows all my life, seem'd as though I never before realized their

peculiar beauty and character in the landscape. (Some time ago, for an hour, in

a huge old country barn, watching these birds flying, recall'd the 22d book of

the Odyssey, where Ulysses slays the suitors, bringing things to

eclaircissement, and Minerva, swallow-bodied, darts up through the

spaces of the hall, sits high on a beam, looks complacently on the show of

slaughter, and feels in her element, exulting, joyous.)

Gazing from picturesque frames of elongated double-panes through lenses with tear drops from showers where clouds joyously release droplets of spherical perfection, I search. Inquiring, Droplets, after years of personified roses becoming roses then love then roses then love twisting and blooming, Who, must I thank for the droplets?

"I thank rain for rain," Wind says.

Thus rain

tones change

rain pauses

clouds hover

as if waiting...

Who and No One thankfully thanking

rain, tones change, rain, tones change

Gazing from picturesque frames of elongated double-panes through lenses with tear drops from showers where clouds joyously release droplets of spherical perfection, I search. Inquiring, Droplets, after years of personified roses becoming roses then love then roses then love twisting and blooming, Who, must I thank for the droplets?

"I thank rain for rain," Wind says.

Thus rain

tones change

rain pauses

clouds hover

as if waiting...

Who and No One thankfully thanking

rain, tones change, rain, tones change

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)