One of the most important elements to a poem is the speaker, and who the speaker is speaking to. This may be found in a variety of ways, either through direct evocation (such as a speaker stating "you"), or through implicit undertones (for example, addressing readers as a group rather than an individual). Whitman's narration technique is somewhat complicated, as he addresses both a personified "you," "O ever-returning spring! trinity sure to me you bring" and then his lover directly "Where amid these you journey, With the tolling, tolling bells’ perpetual clang." Here, Whitman utilizes "you" in two extremely divergent ways. The first, directed toward "Spring," appears to be the poems muse-like evocation, as discussed more in depth in my last post. The second, directly addressed toward his lover, which allows the reader to temporarily remain in his lovers shoes, with the poet speaking directly toward them.

Rukeyser, to contrast, does two things Whitman almost never, ever does. First, she creates group differences. "These roads will take you into your own country." Where "your own country" obviously separates the audience into two separate groups, those of her country, and those of another. Whitman does not do this, not even in Leaves of Grass, instead, Whitman tries to unify. Both are effective for their own purposes, of course, Whitman provides a type of bond with his reader, whereas Rukeyser's provides two lenses through which to understand the poem, seemingly, an outsider and an insider.

These two show the significance of not only a poet's speaker, but a speaker's target audience, and also the ways in which that audience is characterized. Obviously, each technique will evoke a varying response from the onlooker, it becomes an authorial decision. Either you try to unify an outsider (this being an audience member from outside of ones own country), or you try to celebrate these differences. Granted, there are those who might wish to attack such differences, however, such negativity hardly deserves mention. Regardless, although I dislike comparing the effectiveness of two poets, I believe Whitman's evokes a more powerful and positive response (though not necessarily due to their evocation of "you"), mostly because Whitman isn't speaking about warring with another.

The two come to fairly similar conclusions regarding the speakers understanding and acceptance of death. Whitman finds a way to celebrate it, deciding through it all, his lover will live always, forever reborn inside of his own heart. Rukeyser, too, places the dead into a category of "unending love." Also, the two compare death to a plant, a useful vehicle for a metaphor in this case because, they, like a feeling, go through several rebirth cycles.

Monday, April 23, 2012

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

When Lilacs Bloom

Whitman's elegy entitled When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom'd is attempting to grapple with the vastly complicated issue of death. The poem's initial stanza cycles betwixt two contrasting ideas, spring and mourning. The vehicle of spring is utilized to provide the reader with a way to cope with death- rebirth. Lilacs, flowers, and spring are well known for their cyclical nature- they die, and are then reborn. These flowers are symbolic for this living condition; the recycling nature of Earth. However, Whitman uses this semi-ironically; evoking Spring, typically a season known for its rebirth principles, its newness, and its freshness, then counter-balances this with death, mourning, and despair.

"O ever-returning spring! trinity sure to me you bring;

Lilac blooming perennial, and drooping star in the west,

And thought of him I love." (Lines 4, 5, and 6).

Here, Whitman evokes Spring, his poem's natural muse, and also "him I love," his human muse. By doing this, Whitman devises a technique for coping with the loss of the latter. He seems to be presenting the idea that like his natural muse,which is ever-returning, so will his love. His love thus shall become ever-returning, ever-reborn, ever-true- blooming like a lilac in Spring.

"Must I leave thee, lilac with heart-shaped leaves?

Must I leave thee there in the door-yard, blooming, returning with spring?" (Lines 196 and 197).

Late in the poem, Whitman proposes two questions, exposing the narrator's concerns with the loss of his lover. Love, after you have died, must I leave you behind? Or will you once again bloom, away from me, returning with spring? At the very end of the poem, Whitman answers his narrator's questions, "Lilac and star and bird, twined with the chant of my soul..." He concludes that even after losing the lilac and his lover, they shall become ever intertwined with his soul.

Coping with death is a theme transcendent in literary history. Modernity has begun to recycle this theme as well, including a plethora of poems responding to the tragedy of 9/11. Two examples of poets responding to the events are Robert Pinsky's 9/11, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti's History of the Airplane.

Ferlinghetti's poem recounts the history of the airplane, both with respect to tragedy and joy.

http://www.corpse.org/archives/issue_11/manifestos/ferlinghetti.html

Pinksky's touches on firefighters writing social security numbers on their arms, Colonel Donald Duck, the narrative of Fredrick Douglass, and mystic masonic totems. And, quite simply, does it beautifully.

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/entertainment/july-dec02/9-11_9-11.html

Ferlinghetti's poem also compares and contrasts two diverging ideas, peace with tragedy. Similar to Whitman's poem, there is a type of irony. The Wright Brothers, who invented their machine for peace, create a vehicle for war. This is, of course, one of the tragedies to the living condition- often our expectations and intentions sadly turn into something else, even while someone else is striving to achieve similar ends. Even the 9/11 tragedy was a group of people striving for peace, they just had an entirely different perspective on how to achieve that peace. It is unfortunate that some believe violence, destruction, or war will ever bring about peace. Ferlinghetti's poem evokes powerful imagery in its climax, reminding us of 9/11's complete and utter sadness,

"There is chaos and despair

And buried loves and voices

Cries and whispers

Fill the air

Everywhere"

"O ever-returning spring! trinity sure to me you bring;

Lilac blooming perennial, and drooping star in the west,

And thought of him I love." (Lines 4, 5, and 6).

Here, Whitman evokes Spring, his poem's natural muse, and also "him I love," his human muse. By doing this, Whitman devises a technique for coping with the loss of the latter. He seems to be presenting the idea that like his natural muse,which is ever-returning, so will his love. His love thus shall become ever-returning, ever-reborn, ever-true- blooming like a lilac in Spring.

"Must I leave thee, lilac with heart-shaped leaves?

Must I leave thee there in the door-yard, blooming, returning with spring?" (Lines 196 and 197).

Late in the poem, Whitman proposes two questions, exposing the narrator's concerns with the loss of his lover. Love, after you have died, must I leave you behind? Or will you once again bloom, away from me, returning with spring? At the very end of the poem, Whitman answers his narrator's questions, "Lilac and star and bird, twined with the chant of my soul..." He concludes that even after losing the lilac and his lover, they shall become ever intertwined with his soul.

Coping with death is a theme transcendent in literary history. Modernity has begun to recycle this theme as well, including a plethora of poems responding to the tragedy of 9/11. Two examples of poets responding to the events are Robert Pinsky's 9/11, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti's History of the Airplane.

Ferlinghetti's poem recounts the history of the airplane, both with respect to tragedy and joy.

http://www.corpse.org/archives/issue_11/manifestos/ferlinghetti.html

Pinksky's touches on firefighters writing social security numbers on their arms, Colonel Donald Duck, the narrative of Fredrick Douglass, and mystic masonic totems. And, quite simply, does it beautifully.

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/entertainment/july-dec02/9-11_9-11.html

Ferlinghetti's poem also compares and contrasts two diverging ideas, peace with tragedy. Similar to Whitman's poem, there is a type of irony. The Wright Brothers, who invented their machine for peace, create a vehicle for war. This is, of course, one of the tragedies to the living condition- often our expectations and intentions sadly turn into something else, even while someone else is striving to achieve similar ends. Even the 9/11 tragedy was a group of people striving for peace, they just had an entirely different perspective on how to achieve that peace. It is unfortunate that some believe violence, destruction, or war will ever bring about peace. Ferlinghetti's poem evokes powerful imagery in its climax, reminding us of 9/11's complete and utter sadness,

"There is chaos and despair

And buried loves and voices

Cries and whispers

Fill the air

Everywhere"

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

Updating Updates!

To explore Whitman further, and to also dabble into his stance on homosexuality, I'm thinking of crafting some type of short story- embedding quotes and details from the poem as well as seeking to enhance the tone, themes, and motifs. I believe this would be an interesting story, both in terms of exploring the speaker's sexuality, as well as the secretive nature of their meeting in the bar. I'm a huge fan of secret romances, so I think it could be a powerful story.

A GLIMPSE, through an interstice caught,

Of a crowd of workmen and drivers in a bar-room, around the stove,

late of a winter night--And I unremark'd seated in a corner;

Of a youth who loves me, and whom I love, silently approaching, and

seating himself near, that he may hold me by the hand;

A long while, amid the noises of coming and going--of drinking and

oath and smutty jest,

There we two, content, happy in being together, speaking little,

perhaps not a word.

By, Walt Whitman

A GLIMPSE, through an interstice caught,

Of a crowd of workmen and drivers in a bar-room, around the stove,

late of a winter night--And I unremark'd seated in a corner;

Of a youth who loves me, and whom I love, silently approaching, and

seating himself near, that he may hold me by the hand;

A long while, amid the noises of coming and going--of drinking and

oath and smutty jest,

There we two, content, happy in being together, speaking little,

perhaps not a word.

By, Walt Whitman

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

Peter Doyle

One of the attributes to a famous artist most overlook is their humanness, the attributes that make us a human being. Did Shakespeare have a best friend? Did Chaucer enjoy drinking tea? Did Homer ever have a lover? Artists become a figure of greatness to most, a position which tends to dehumanize them.

Peter Doyle and Whitman were intimate friends, so intimate, some believe the two may have been lovers. After reading about Doyle's life, it becomes apparent why a writer would have cherished him, not only as an individual, but also as a type of muse. Doyle, a commonly educated man, was a soldier, prisoner of war (which he escaped from), an attendee of the play where Abraham Lincoln was shot, a street car worker, a railroad worker... Basically, Doyle was a figure Whitman could view as a flawless American, one who experienced nearly every huge historical feat of the century.

The two sent a group of letters back and forth, which were stored and later published. One interesting aspect to this publication is the type of fame Doyle was able to recieve merely by being a friend of Whitman. Reviewers of the letters initially wished there were more written by Doyle! It's fairly interesting to think a relatively unliterate man draws forth more reader interest than one of the most famous poets history has to offer.

Regardless of fame and historical acclaim, the two had one of the best relationships in literary history. Doyle's emotional attachment to Whitman is, to say the least, touching. Doyle recounts his attempts to keep Whitman alive even after death, merely to be close to the man.

"I have Walt's raglan here [goes to closet—puts it on]. I now and then put it on, lay down, think I am in the old times. Then he is with me again. It's the only thing I kept amongst many old things. When I get it on and stretch out on the old sofa I am very well contented. It is like Aladdin's lamp. I do not ever for a minute lose the old man. He is always near by. When I am in trouble—in a crisis—I ask myself, 'What would Walt have done under these circumstances?' and whatever I decide Walt would have done that I do."

Upon his passing, Whitman gave Doyle a silver watch. This silver watch signifies not only the lasting friendship of the two, but also stands as a symbol for the duration of time Whitman and Doyle had been friends. A fairly beautiful friendship, one which shines brighter than silver and is worth more than gold.

Peter Doyle and Whitman were intimate friends, so intimate, some believe the two may have been lovers. After reading about Doyle's life, it becomes apparent why a writer would have cherished him, not only as an individual, but also as a type of muse. Doyle, a commonly educated man, was a soldier, prisoner of war (which he escaped from), an attendee of the play where Abraham Lincoln was shot, a street car worker, a railroad worker... Basically, Doyle was a figure Whitman could view as a flawless American, one who experienced nearly every huge historical feat of the century.

The two sent a group of letters back and forth, which were stored and later published. One interesting aspect to this publication is the type of fame Doyle was able to recieve merely by being a friend of Whitman. Reviewers of the letters initially wished there were more written by Doyle! It's fairly interesting to think a relatively unliterate man draws forth more reader interest than one of the most famous poets history has to offer.

Regardless of fame and historical acclaim, the two had one of the best relationships in literary history. Doyle's emotional attachment to Whitman is, to say the least, touching. Doyle recounts his attempts to keep Whitman alive even after death, merely to be close to the man.

"I have Walt's raglan here [goes to closet—puts it on]. I now and then put it on, lay down, think I am in the old times. Then he is with me again. It's the only thing I kept amongst many old things. When I get it on and stretch out on the old sofa I am very well contented. It is like Aladdin's lamp. I do not ever for a minute lose the old man. He is always near by. When I am in trouble—in a crisis—I ask myself, 'What would Walt have done under these circumstances?' and whatever I decide Walt would have done that I do."

Upon his passing, Whitman gave Doyle a silver watch. This silver watch signifies not only the lasting friendship of the two, but also stands as a symbol for the duration of time Whitman and Doyle had been friends. A fairly beautiful friendship, one which shines brighter than silver and is worth more than gold.

Rereviewing Reviews and Reviewers

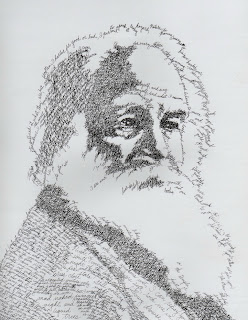

For my next major project, I shall either approach the reviewers reviews of Whitman's Leaves of Grass from a few specific schools of criticism, or I will paint a type of word portrait of Whitman utilizing text from his Leaves of Grass. While the first will expand my knowledge of modern day techniques of criticism, the second will increase my knowledge of Leaves of Grass through a careful selection of thematic phrases, while also developing my artistic abilities. To expand on both ideas, I wish to approach reviews of Whitman's text because it becomes a type of exponential learning, reflecting on anothers reflections. Also, varying forms of criticism are fairly central to the modern day literary scene, such as deconstructionism, new historicism, formalism, and even types of psycho-semantics. This would prove helpful because I would become more familiarized with directions literary critics take while sorting through literary works. A painting, however, could prove extremely aesthetically pleasing, while also promoting this type of hybridity which overwhelms todays artistic front. Combining various artforms, here poetry and painting, would expand both markets, as well as allowing me to freely delve between fairly rich artistic material. Artistically speaking, there are a series of techniques which would be integrated to derive a completely unique creation. My only limitations are my current lack of photoshop, which would open doors to craft a type of 3D image (possible utilizing calculus, too, just less precise).

Would require further research of outside critical techniques, or a focus primarily on Whitman's text. Essentially, each would prove to be a powerful learning process, they simply focus on two different types of art- one visual, and one textual.

Would require further research of outside critical techniques, or a focus primarily on Whitman's text. Essentially, each would prove to be a powerful learning process, they simply focus on two different types of art- one visual, and one textual.

Monday, March 12, 2012

Whitman's Popularity

Word portraits are the classiest, let's be real. Whitman's face created from the face of words thrown across a page- what could be more hip? The portrait, aside from being unparalleled in its level of coolness, reinterprets poeticism in an extremely unique way... Here, a poet is viewed as a composition of his words, a carefully shaped and precise selection composing a snapshot image of themes and poeticism. Most view poems as extensions, here, the artist reinterprets poems as a composition of a poet.

Artist of Word Portraits- John Sokol, Alyssa Pelletier

http://www.johnsokol-artist-author.com/index.html

http://alyssapelletier.com/

Martin Tupper: Didacticism

Martin Tupper, a poet from Whitman's time era, represents a genre paralellism- IE a style of writing growing onto another branch of poetries trunk. Martin Tupper focused on morality, a didactic approach toward teaching masses stronger moral values than was prevalent- a difficult yet noble cause. Whitman's own genre, mostly free-verse celebratory poetry, tends to stray away from overt didacticism, focusing on celebrating the positive aspects of life rather than critiquing moral mistakes of the past. These two writers provide valuable insight toward what made Whitman popular, canonized, and remembered, whereas Tupper remains relatively in the wake of Whitman's allegorical power-boat. I would argue this happened from something fairly and simply- genre. Whitman strayed away from teaching entire groups morality, something most believe to be intrinsic, innate, and extremely relative. People, generally, dislike being told how to behave, what actions are socially "correct" and "incorrect," or to have another bash each decision that they make with an air of sophisticated morality. Whitman's morals are weaved into the threads of his texts, being exposed through character actions, narrative restraint, dictorial selection; whereas Tupper provides clear religious and moral instructions,

"Despise not, shrewd reckoner, the God of a good man’s worship,

Neither let thy calculating folly gainsay the unity of three:

Nor scorn another’s creed, although he cannot solve thy doubts;" (Of a Trinity).

His work tells how, it does not recount how. Whitman's tales, on the other hand, recount a narrative structure, a way of life, an individual experience- He does not appear to wish for his readers to behave in the same manner, no, he celebrates their differences. Whereas Martin Tupper seems to wish for each reader to follow the same moralistic and religious guidelines as his narrator. These two differences explain not only what gained Whitman more support in his generation, as well as those which followed, but also divulged important information as to persuasive and rhetorical techniques utilized by institutionalized churches (represented through Tupper). Rather than celebrating differences and recounting favorite personality and charactorial types, it provides a routine, a copy-pasted structure of similarness, it strives to craft identities to not necessarily become identical, no, for this would be too obvious and perfect to them, but instead to formfit each individual to follow structural and overarching guidelines. Whitman gained support because he restrained from telling people how to behave, whereas Tupper gained some sort of inner-satisfaction supporting an institutionalized life path. Each benefits in their own respect, however, Whitman seems to have attained the popular vote, so to speak.

"Despise not, shrewd reckoner, the God of a good man’s worship,

Neither let thy calculating folly gainsay the unity of three:

Nor scorn another’s creed, although he cannot solve thy doubts;" (Of a Trinity).

His work tells how, it does not recount how. Whitman's tales, on the other hand, recount a narrative structure, a way of life, an individual experience- He does not appear to wish for his readers to behave in the same manner, no, he celebrates their differences. Whereas Martin Tupper seems to wish for each reader to follow the same moralistic and religious guidelines as his narrator. These two differences explain not only what gained Whitman more support in his generation, as well as those which followed, but also divulged important information as to persuasive and rhetorical techniques utilized by institutionalized churches (represented through Tupper). Rather than celebrating differences and recounting favorite personality and charactorial types, it provides a routine, a copy-pasted structure of similarness, it strives to craft identities to not necessarily become identical, no, for this would be too obvious and perfect to them, but instead to formfit each individual to follow structural and overarching guidelines. Whitman gained support because he restrained from telling people how to behave, whereas Tupper gained some sort of inner-satisfaction supporting an institutionalized life path. Each benefits in their own respect, however, Whitman seems to have attained the popular vote, so to speak.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)